Victory by Mail

V-Mail reproduction

Staying in Touch during War

Imagine a world with no laptops, internet, mobile phones, e-mails, texts or social media. Imagine sitting at a desk with stationery and fountain pen, to hand-write a letter; seal, address and stamp it; then, put it in the mail. That’s the moment the agony of waiting would begin—waiting for the penned words to be put in the correct mail bag, loaded onto ship or airplane, and carried to your loved one. After that, waiting for the long voyage of the reply. This was the everyday reality of people during World War II.

Millions of families were separated, not by choice—the fortunate ones were able to send and receive letters. These wood-pulp emissaries went by the millions around the world, often taking months to be delivered. Everyone from the frailest grandparent to the toughest combat soldier longed for them. They were a pitiful substitution for lost moments together, yet powerfully essential to morale. Sometimes they were the only way military personnel learned about their newborn children, the death of loved ones or other significant events they missed.

Microfilm to the Rescue

During wartime conditions, letters were competing with many other things for traveling space. Food, supplies, munitions and troops also required cargo room. But the mail had to carry on—it was as essential for souls as C-rations were for bodies. No matter how far-flung the location of troops, whether in deserts, islands, jungles or the deep blue sea, letters from home simply had to get there.

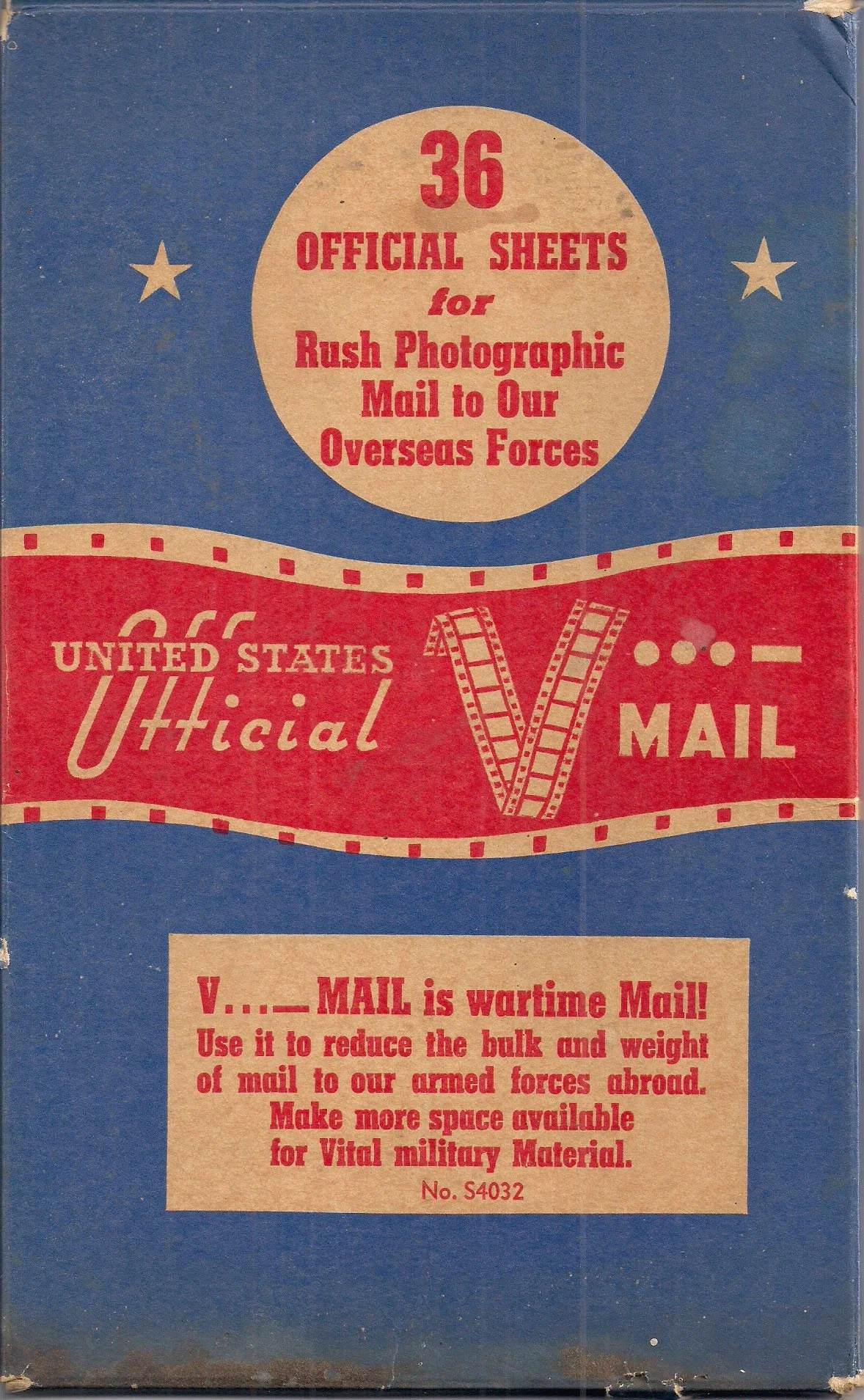

In a world upended by war, people were willing to try new things to keep communication lines open. In this case, the postal services in both Great Britain and the United States resorted to microfilm, a method being used by banks since the 1930s. Letters could be copied and shipped, then printed at their destinations. In Britain the system was called AirGraph; in the United States, Victory Mail, or V-Mail.

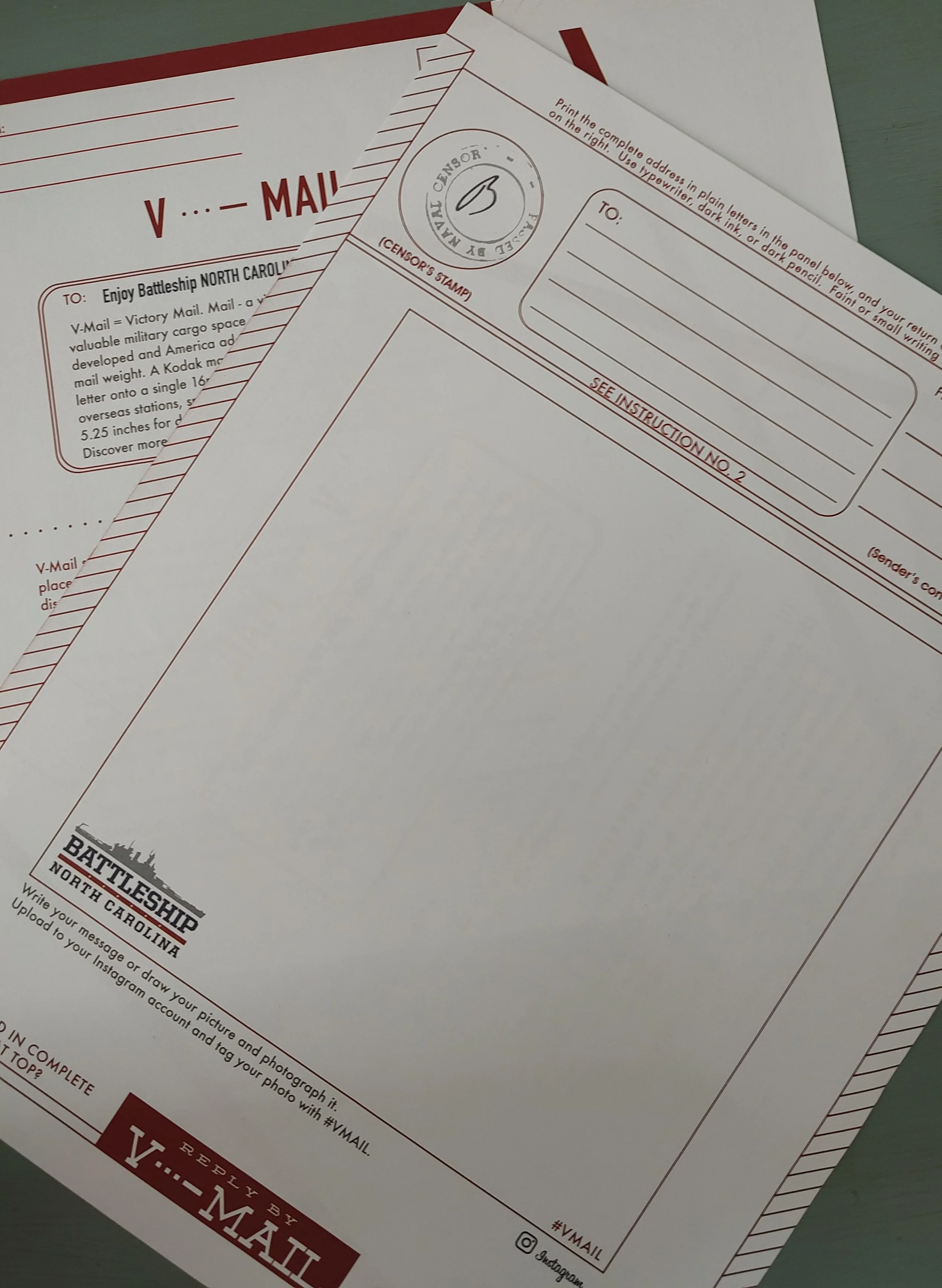

To use this system, people used special pre-printed stationery. One side had space for a letter of about 300 words along with addresses and an area for the censor’s approval. The other side included instructions and a place for stamps. The one sheet of paper was both letter and envelope.

AirGraph service began in 1941 and was quickly adopted by the US Post Office as V-Mail service. Letters went to processing centers where they were transferred onto a single 16mm movie frame! At the destination, the letters were re-printed for delivery. This method saved an incredible amount of weight and space, was more secure, and was faster. More than a billion letters were delivered by 1945 when the microfilm service ended.

These days it is difficult to imagine waiting for even the faster microfilmed mail. Should world events cause a loss of instant communication in future, I’m glad our forebears showed us another ingenious way to stay in touch. V-Mail and AirGraph letters helped keep the home fires burning until the flames of war finally ended.

References

BATTLESHIP NORTH CAROLINA, 1 Battleship Road Wilmington, NC 28401 USA

V-MAIL, Historian, United States Postal Service, July 2008.

“For I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Romans 8:38-39